By Virginia Gallagher, Raglan & District Museum Society

(Originally published in the Raglan Chronicle, 14 May 2015)

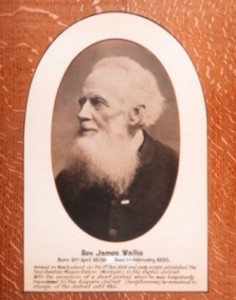

April 2015 marks 180 years since the Rev James Wallis arrived in Raglan to set up a Mission Station at Te Horea. He was to serve as a missionary in the Whaingaroa area for 30 years, except for 2 years when he was stationed at Tangitororea in Northland. How many of us today could survive as the Wallis family had to live in the early days? Early missionaries were jacks of all trades, having to build their own houses, barter for food, cook over an open fire, and if required to travel overland, to do so on foot.

In 1833 at the age of 24, Rev Wallis was a candidate for the ministry of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in England, and in April the following year he was ordained a minister. Shortly after his ordination, he married Mary Ann Riddick and having volunteered to undertake missionary work, Rev and Mrs. Wallis set sail for Hobart, where they waited some weeks before sailing on the Triton for the Hokianga. They arrived at the mission station at Mangungu and although Rev Wallis was keen to start evangelical work, he was pressed into service helping to build a large weatherboard church.

In April 1835, the Wesleyan Mission decided it was time to establish two mission stations in the Waikato, one at Whaingaroa and one at Kawhia. Rev and Mrs Wallis along with Rev and Mrs Whiteley then sailed down the coast to Kawhia, where a crowd of over 1000 waited at Kawhia to celebrate their arrival. Mrs Wallis stayed in Kawhia, while the Rev Wallis, accompanied by a Maori guide, walked 30km to Whaingaroa. Initially Wallis only had a small raupo hut, about 3m x 2m to live in. A Mission house was completed a few weeks later, and Mrs Wallis was fetched from Kawhia by about a dozen natives, who carried her in a sedan chair made from vines and branches of trees. She was carried to Whaingaroa in triumph, the first white woman to come to that part of the country.

The building of the mission house took a lot of Wallis’s time, but he still preached the gospel with the aid of an interpreter, John Leigh. By January 1836 many local Maori had converted to Christianity, including the great chief Te Awaitaia, who at the time of his baptism took the name of William Naylor, or Wi Neera. Between 400 and 500 worshippers attended Sunday services. Meetings were held every night and children attended Sunday School on Sundays. Although Wallis initially despaired at ever becoming fluent in the Maori language, it was not long before he was able to preach in fluent Maori.`

In May 1836, Wesleyan Secretaries in London advised that the Church Missionary Society intended to occupy Whaingaroa, and Wallis was to withdraw from the area. This caused great dismay among Maoris and missionaries, but Wallis had no option but to obey instructions.

In June the Wallis family left for Tangiteroria in Northland, where Wallis’s first job was to build himself a house. After 12 months of ‘fruitless labour’ Wallis reported that the Tangiteroria Maori ‘had no desire for religious instruction’. Twice, visiting Whaingaroa Maori encouraged him to return as they were still attending worship and learning to read and write under the leadership of their own people. As the Church Missionary Society had not occupied the area by October 1838, Wallis was granted permission to return to Whaingaroa.

In March 1839 the barque Elizabeth arrived in Raglan where all the Wallis’s possessions were unloaded onto the beach. The old mission house at Te Horea had fallen into disrepair. Land was bought at Nihinihi for a new mission station. In the meantime, a rough shelter was arranged for the family, now with three children, on the beach. Their four poster bed was covered with timber and blankets, and packing cases were placed around it to form a shelter from wind and rain. A large raupo church was built at Nihinihi, and a weatherboard house later constructed. Wallis wrote that in the five years he had been in New Zealand he had spent most of his time building somewhere to live, and he had had little opportunity to undertake missionary work. On the first Sunday after his return to Whaingaroa, Wallis preached to a crowd of 500, baptised 65 and married 23 couples.

In 1840 Wallis was asked to go to Port Nicholson (Wellington) as it was proposed to establish a mission station there. Wallis was asked to visit in an advisory capacity. As there was no regular shipping service between Manukau and Wellington, Wallis, accompanied by several Maori, undertook the journey on foot. The return trip took 3 months; most of this time was spent in walking there and back. They travelled down the coast and fording rivers, negotiating sand hills and seemingly impassable cliffs were all part of the experience.

Wallis was deeply concerned about education, and in 1844 a school was established in Auckland to be called the Wesleyan Native Institute. One of its first pupils was a son of Wi Neera. He also agitated for a school for the children of missionaries. Often the mission outposts were in remote places where there was no opportunity for schooling or interaction with other children. Eventually the Wesleyan College and Seminary opened in Auckland with 40 children in residence, from almost every mission station in the Pacific. In the next few years several of the Wallis children attended the school.

In 1863, after nearly 30 years as a missionary, Wallis accepted a posting to Onehunga. Now aged 54, he was saddened greatly by the turn of affairs brought on by the land wars. Large numbers of Maori had been dispossessed of their land, and former settlements with large Maori populations had vanished or become small unimportant villages. His children were now at school in Auckland, engaged in missionary work in the Pacific Islands, or engaged in farming activities. The settlers of the district were sorry to see the Wallises go. The Maori of the area presented Wallis with an address in the form of a lament, which Wallis found deeply moving.

Wallis found the transition from Maori missionary to the European ministry difficult; he had not kept up the practice of preaching in English. After three years at Onehunga he transferred to the Pitt Street Methodist Church. In 1868 he became a supernumerary minister, a post he held for 27 years. By now he had outlived most of his contemporaries. With his flowing white beard, he became affectionately known as Father Wallis. He died in 1895, his wife Mary Ann having predeceased him 2 years previously, and having outlived four of his nine children.

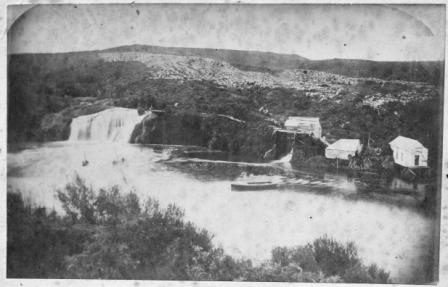

In 1852 Wallis bought 200 hectares of land at Okete, and two sons, William and Thomas, began to clear the land and create a farm. It had been intended to run a flour mill at Okete, but instead in 1868 a very successful flax mill was established. Once the supply of flax was exhausted, the mill was converted to provide electricity for the family. Wallis also bought land in Wallis Street. Warahi Park in Wallis Street, on land donated by the Wallis family, is now a children’s playground.

Joan Hawken (nee Wallis) and her father Orton Wallis at the Raglan Remembers WW1 exhibition – Photo by Kaz

Today in 2015 there are still direct descendants of James and Mary Ann Wallis living in Raglan. In 1988 members of the Wallis family compiled a ‘Family Circle’, which lists the names of over 1000 descendants from James and Mary Ann. At the end of Bow Street, a memorial seat faces across the harbour to Te Horea, an arrow pointing to the site of the original mission station. On the right hand side of Wainui Road, just up the hill from the one way bridge stands a monument which marks the site of the Nihinihi mission station.